Discourses on Love

Christopher Matthews’s Desire Cycle

Arabela Stanger

Plato’s Symposium opens with an elaborate gossip chain. In a dizzying preamble to the text, our narrator Apollodorus explains how he and others came to know about the celebrated speeches on love given at a drinking party hosted by the tragic poet Agathon. This back-story to the central dialogue consists of a rapid word-of-mouth relay among a cast of men all intensely curious to know just what was said and done, at that party, about love. As a way towards Christopher Matthews’s Desire Cycle (2017–2024), a rotation of three dance works inspired in part by Plato’s text, it’s worth charting this relay in full for the way it implies a certain kind of cycling desire:

Aristodemus is the first link in the chain. He was actually there at Agathon’s party, which took place long ago as it turns out, when several ‘speeches in praise of love’ were delivered by Socrates and other guests. Aristodemus then repeated these speeches to Apollodorus who, seeking accuracy, circled back to fact-check with Socrates himself. Apollodorus then re-told the speeches to Glaucon during a walk they took together on the road from Phalerum to Athens. Glaucon for his part had already been told about the speeches by Phoenix, son of Philip, who had also been told about them directly by Aristodemus. Apollodorus recounts this rumour-mill before finally agreeing to recite the story yet again to an unnamed acquaintance. This is a man to whom Glaucon had originally mentioned the speeches, peaking his interest enough for him to hail Apollodorus in the street (Apollodorus, O thou Phalerian man, halt! ) to ask what he knew, a request initiating a retelling of the whole affair including, chiefly, the after-dinner discourses on love. [1]

There is something about these gossipy beginnings of Plato’s love philosophy that speaks to the worlds created in Lads (2017/18), My body’s no.1 (2022), and Act 3 (2023/4), all dance installations dealing with economies of queer desire and all implying the relational dynamics and intense erotic curiosities modelled in the Symposium’s preamble. The who-said-what-to-whom, hazy quality of that preamble scene in ancient Athens does two things to the way people talk about love that show up also in Desire Cycle’s choreographies and its modes of performance and spectatorship. 1) The gossip chain communalises the central subject of Plato’s text. Love, in the story relayed in the preamble, had been communalised already of course in the seven-way dialogue through which Socrates and his interlocutors explored their subject after dinner, a discursive community that is then continually opening-up as more and more men join the cycle of gossip. 2) This way of sharing ideas about love also then expands time, drawing out the party speeches over months, maybe years and possibly across generations, so that the dinner guests’ original love discourses travel in new voices and through history.

This communalising and time-expanding meditation on love gives sight of a kind of homoerotics often found in and hotly debated in relation to Plato’s Symposium. As classicist and queer theorist David M. Halperin has explained of the preamble: “Gossip itself reflects the operation of erós,” creating a “a force-field of desire” around the thing being gossiped about – here, the speeches at Agathon’s party.[2] Knowledge of those speeches is then held, coveted, shared and insistently sought out by the men of Athens. These same forces of communal curiosity, operating erotically through desires harboured and distributed, describe the worlds of Matthews’s three desire dances: where dance-historical and art-historical stories about love cycle into the present through performance scenarios manifesting various force-fields of desire.

Fleeting Histories and Dance Gossip

Moving through dances for three stages of life – for the youth (MBNo1), for the ‘arrived’ into adulthood (Lads), and for elders (Act 3) – the dances of Desire Cycle all stage time-expanding communions on queer love. Like Plato’s love-tellers and gossipers, the dancers with whom Matthews made this cycle are rarely on their own when performing these works, which are presented in installation format with the audience close-by and all around; they are always in a process of exchange with one another in the dance, even if and maybe even more so because they never make eye contact with their roaming audience. Like Plato’s love-tellers and gossipers, too, the dance works themselves are never really on their own either, communing with historic dances, events, characters and real ‘dance people’ constituting what Matthews calls the cycle’s ‘fleeting histories’. Across the works you may or may not catch glimpses of a cast of characters and their work including: U.S. modern dance utopia Jacob’s Pillow, artists and choreographers Ted Shawn, Kenneth MacMillan and Tino Seghal, queer modernist photography collective PaJaMa, ancient sculpture the Barberini Faun, famous dancer/muses Barton Mumaw and Rudolf Nureyev, and history’s more anonymous dancer/muses from gogo boys to Degas’s ‘little dancer aged fourteen’.

I am fascinated with Desire Cycle’s fleeting histories and how the transitory presence of these dance and visual-cultural ancestors creates force-fields of desire in the works. Following that fascination into this piece of writing, I attempt here to trace, entirely incompletely, some of the intergenerational and transhistorical communions involved in Desire Cycle, and which seem to me to make up this choreographic cycle’s queer dancerly discourses on love.

***

In doing this, I am calling back to another gossip-session, one I shared with Matthews – Chris from hereon in, to honour the tone of our exchange and friendship – as part of our ongoing practice of being nerdy together about dance history. During this particular session, which took place early in the summer of 2024 in Brighton, Chris and I sat down so that he could tell me about the process of making Desire Cycle, a discussion that in the end saw us obsessing over some dance-historical encounters that were alive to Chris while he was making these dances.

I was meant to be taking solid notes through that conversation. But what happened instead was something more typical of our dance-history chats: disappearing ideas, tangents, lots of asides, googling what people looked like, checking dates of things, inspecting images, laughing at rumours, such that my notes in the end were really no good, but my orientations towards fleeting dance-history moments were. This, I think, speaks to the atmospheres of the desire dances themselves.

Here are three of those fleeting moments:

tea-service in bathrobes and star-gazing at Jacob’s Pillow;

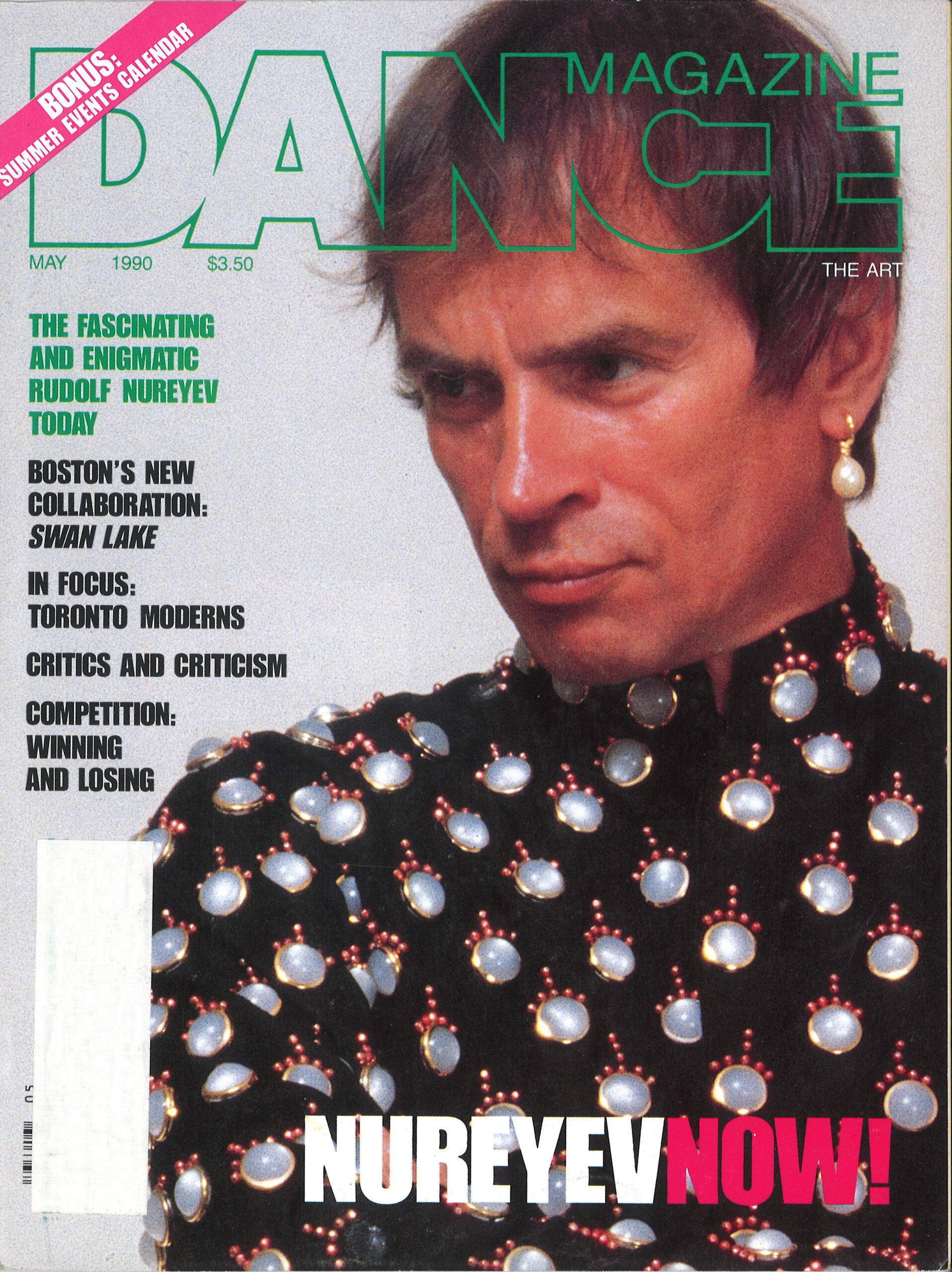

a mysterious image of Nureyev covered in pearls;

an un-sexy kiss in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet.

Staying within the force-field of desire for those histories created in our dance gossip session, and in the spirit also of Plato’s second- and third- hand stories, I take these moments as starting points for thinking about the erotics of Desire Cycle, reflecting in dialogue with Chris but also with ideas shared by two of the people who performed these works: J. Neve Harrington and Donald Hutera. In the fleeting moments I name above, each one pointing to intergenerational dance communions, I offer entry points into Desire Cycle’s three works, moving through the cycle’s internal chronology (youth-to-elders) to trace their respective and shared choreographic discourses on love.

My Body’s Number 1 - Serving the Self at Jacob’s Pillow

Chris recalled to me a turning point in his life as a young dancer. In 1997, aged 16, he was driven the 10-hour drive by his big brother from Virginia Beach, Virginia, to Jacob’s Pillow in Massachusetts for a summer dance programme. They arrived, much to the surprise of his brother who was not involved in ‘modern dance’ like Chris was (the latter unique in his family in this respect), to the offering of a bathrobe. This robe was to be donned by Chris who was promptly invited to join the other dancers in serving tea and cucumber sandwiches to guests on the lawn. This, it turned out, was a decades-long practice at Jacob’s Pillow, initiated by Ted Shawn in 1933 as a canny (and at that point quite urgent) fundraising effort where his all-men dance troupe would serve the Berkshire locals and would-be sponsors their tea and sandwiches, dressed in terry-cloth robes, before performing for the same guests in the “makeshift barn” on site.[3] This history of serving the self at Jacob’s Pillow prompted Chris and me to share stories of our personal experiences of being a dancer-as-service-worker, acting as we respectively did on occasion as trained bodies on display for the transfer of money which invariably did not go to us, but to the under-funded institutions we were representing. (My own choice memory, for instance, is when I danced as a teenaged ballet student in a tutu and pointe shoes, on a fluffy carpet at the high-end London hotel Claridges’ Children’s Christmas party, c.2000, an engagement that must have commanded a decent fee that went not at all to me but, as far as I know, to the ballet conservatoire at which I was then training. I recall being ushered after the show into a side room, alongside a python and its handler, so that children could touch my costume and thinking, ‘how did I end up here?’, even from my position of relative comfort and protection.)

As Marie Geneviève van Goethem, the legendary but frequently unnamed young dance worker, sex worker and model for Degas’s ‘little dancing girl’ knew full well, dancers both command attention and generate returns in varying types of service economy but so often receive little to no remuneration for that labour.[4] Returning to Chris’s original memory of the tea-service at Jacob’s Pillow, the practice of using dancers’ work to fund the operations of an institution from whose success those dancers do not consistently materially benefit, was of course not the only form of extractive practice established at The Pillow. As Lionel Popkin points out, calling to vivid arguments made by a range of artists and researchers, Shawn’s avowed and well-intentioned interest in “using the techniques” of South Asian and East Asian dance to “enrich” (in Shawn’s terms) the Modern Dance culture developed at The Pillow, reveals “a process by which the western world takes what it wants from the rest of the globe,” a dynamic, as Popkin explains, that “is commonly called colonialism.”[5] Who and what was being served at this modern dance utopia, for whose delectation and for whose sustenance?

But dancers at Jacob’s Pillow, as with anywhere else, enact forms of agency in the face of potential exploitation or extraction, serving their own push-backs and serving their own ideas of what dance can be: be it the critically incisive schoolings given by Indian and Indian diaspora artists who conversed with audiences after their performances at The Pillow (and I recommend listening in full to Popkin’s podcast episode on this subject, to hear recordings of these schoolings), or the kinds of unofficial, and hidden, queer worldmaking at this site that was both known for its history as a “gay utopia” and contoured, as all cultural centres are, by institutional homophobias. [6] It was in that same summer programme initiated by the tea-serving, in fact, that Chris also recalls experiencing his first recognition of queer community: not on the lawn handing out sandwiches to patrons, but at the (forbidden) nightly gatherings on the open-air Inside/Out dance stage perched on the side of the mountain, where some of the summer students snuck out, smoked, lay back and looked together at the stars.

Chris’s snapshot memory from that summer of 1997 at Jacob’s Pillow. Summer programme dancers pose with dancer-choreographer-teacher Barton Mumaw. (Chris is bottom right)

Bringing himself back to the feeling of that moment, Chris recalled to me: “I am in a group including queer men and I am a closeted man. And it is all okay. I didn’t come out. But I felt community and safety. It was such an important summer; it shifted everything for me personally, professionally.” In Hey Boo (2022), another work of Chris’s inspired by this moment and made in the period of Desire Cycle, dancers are costumed in Jacob’s Pillow-esque bathrobes and explore acts of autonomy and queer pleasure that dancers manage to eke out from within the constraints of their working conditions. But it is from in-between these particular twin memories from Jacob’s Pillow – the serving of self to others in the bathrobe and the serving of one’s own desires for a different kind of community while star-gazing – that I understand to be a locus for the emergence of a particular kind of eroticism in MBNo1, one characterised by generosity bound with a logic of refusal.

A duet for two dancers in their early twenties, MBNo1 (2020) was made with and/or has been performed to date by fraserfab, Ryan Kirwin, Benjamin Knapper, Kanis Murillo, Dominic Rocca, and Riley Wolf. Audience members enter the space in which the work is performed to find a sculptural event unfolding before them and around which they can wander, where “two young ballet figures [are] undulating in a trance-like state on two plinths or gogo boy boxes,” raised about four feet off the ground. [7]

fraserfab and Benjamin Knapper performing MBNo1 in 2021. Photograph by Camilla Greenwell.

Having watched this work live and on screen, what always strikes me the most is the gaze of the performers. Their eyes do not leave one another’s through the work. Even when the art of balancing high on the plinth demands peripheral vision, these dancers only have eyes for each other, making a force-field of sorts around their sculptural event. This has the effect, in one sense, of releasing audience members from responsibility for the power-relations enacted in our own acts of beholding these dancers as they move; if no one answers our gaze, can we look on without consequence or measure? I felt the work ask this question of me, many times over, as I watched a live version in 2021. But, calling back to Chris’s memory of summer nights at Jacob’s Pillow, I also think of this mutually magnetic and utterly exclusionary gaze as a kind of queer star-gazing. Just as dancers at The Pillow’s summer programme reclaimed the Inside/Out Stage as a space for their own communal desires, directing their gaze up to the skies (rather than out to the audience as on-stage activity so usually demands) and seeing stars in the process, so the dancers in MBNo1 withdraw their gaze from their expectant audience, fixing instead a mutual and intently focussed gaze upon one another, finding stars in the other, making a force-field of dancing interest and forging a dancer-community not obliged to serve their audience but to serve themselves, plural.

Lads – Nureyev in Pearls

While we talked about Jacob’s Pillow and its histories of gay community – personal and contested, told and un-told – Chris shared an earlier dance memory which felt connected to his community encounter at The Pillow but this time grounded less in physical immediacy than in visual fantasy. “The first time I ever saw a real queerness,” explained Chris, “was the May 1996 cover of Dance Magazine: Nureyev, wearing a black sweater with pearls dropping off of it, and pearl earrings.” Chris and I both spent ages searching for this image. We couldn’t seem to find it and I for one started to doubt that it existed beyond Chris’s imagination, a legitimate dance-encounter in itself. But Chris finally unearthed the cover in an online image search; May 1990 as it turns out. Here it is:

Screenshot of Chris’s image-search showing Nureyev in pearls on the cover of Dance Magazine, May 1990.

I asked Chris what it was about this image that captured him. “Basically it was the first time I saw queerness,” he explained, “and I didn’t know that it was queerness”. “For me, it was a different thing to being a ‘gay male’; there was this elegance and gender fluidity that I had never seen before. There was this masculine and feminine colliding, and that is so where my work is.” The collision of masculine and feminine, in Nureyev’s styling, his posture, his attitude – captured so typically in the pearl photoshoot and expressed more broadly by the way his remarkable kinetic style dissolved the gender binary inscribed through ballet – chimed with me also, as a life-long fan of this dancer.

I too have obsessed over a single image of Nureyev: a black-and-white photograph taken of him by Richard Avedon in the early 1960s, which I had blue-tacked to my bedroom wall alongside assorted musician posters when I was a ballet student. In this image Nureyev is seated, torso bare apart from the straps of his ballet practice-clothes, leaning forward with one arm balanced on his knee, the other cradling the back of his head. What captured me about this image was also its collision of masculinised and femininised corporeal shapes, particularly in the position Nureyev adopts with his upper body. With a perfectly arranged ‘ballet hand’ draping beyond the knee and a breadth across the chest initiated by subtly rolled-back shoulders and a bit of ballet épaulement (where torso, shoulder and neck torque around the spine into a counterposed, showy presentation of the body’s angles and curves), Nureyev’s figure was one I desired for myself both as an expression of my sexual interest but also as a model of how I might move, how I might make shapes, as a young woman ballet dancer. Dance critic Joan Acocella has written about Nureyev as dancer and sex symbol that “an added attraction, for some, was his androgyny.”[8] Nureyev “modelled himself on the female dancers. He cultivated a highly pulled-up torso and did elaborate, wafting arm movements.”. Acocella further reveals that “when he made his début in Giselle, a fellow-dancer said, ‘We had a girl and another girl as the boy’.”[9] Rejecting the queerphobia informing that final phrase and seeking instead, as is modelled so keenly in Chris’s work, a reparative queer choreographics in and through it, it seems important to me that Nureyev ushered in ‘another girl as the boy’ in his stylistic interpretation of the balletic canon’s straight romantic partnership. In this manoeuvre Nureyev skewed the gender binary enshrined in balletic repertoire, collided gendered and sexual orientations through his profound experimentation inside ballet technique, and cultivated new modes of spectacular desire as modern ballet history’s perhaps most compelling performer.

When reflecting on the complex desires (be they sexual, aesthetic, social, or vocational) awakened in both Chris and me, in our own different ways, by our intense curiosities in Nureyev’s image, it is essential to remember that the image-industry surrounding Nureyev, a manufacturing of stardom in which he of course participated, is marked by a particular kind of racialised imagination.[10] After his defection from the Soviet Union to Western Europe in 1961, Nureyev was catapulted into the European and then North American public imagination through abundant forms of orientalist fantasy. Take, for instance, this 1962 review of his first London Le Corsaire (one of nineteenth-century ballet’s most orientalist spectacles) with England’s premier ballerina Margot Fonteyn, with whom he would go on to forge a lucrative partnership: “Fonteyn who, being the least vain and least umbrageous of ballerinas, evidently relishes his exotic, far from submissive partnership.”[11] And also this reflection on the same production, by the Nureyev Foundation itself: “We find him, splendidly barbaric, erotic and feline with Margot Fonteyn as his partner, in a film from 1963.”[12] Typical of the way Nureyev’s ‘gifts to the West’ were framed after 1961, these depictions of an alien, risky but also replenishing kind of sexuality on offer to his white Western ballerinas (and audiences, and fans like Chris and me) satisfy Palestinian scholar Edward Said’s definition of orientalist appetites for ‘the other’, even as Nureyev’s family’s Muslimness is so often erased from romanticised discussions of his Tatar heritage and early life in varying states of poverty in Ufa. Indeed, as Jasbir Puar explains of Said’s discussion of sexuality in the latter’s major work of scholarship Orientalism (1978): “The Orient, as interpreted from the Occident, is the space of illicit sexuality, unbridled excess, and generalized perversion;” continuing, “Said writes that ‘the Orient was a place where one could look for sexual experiences unobtainable in Europe’ and procure ‘a different type of sexuality’,” through the apparatus of colonial mobility.[13] If Nureyev’s image and dancing prompted revelations for generations of dancers and audiences in ‘the West’, offering us different ways of moving through our genders, sexualities and desires, then that legacy is also marked by forms of white imagination, particularly vexed in the Cold War context of his defection from the Soviet Union: a desiring and exoticising imagination Nureyev was able to manipulate through the presentation of his own image, in pearls, in Central Asian fabrics (which he often wore in his later years in his own branch of sartorial orientalism[14]), or simply in his own skin, exposed.

Returning to the work in Desire Cycle that deals most directly with the openings of masculinity into explorations of queerness, sexuality and class through the tool of image-making in dance, I think about Lads (2017) as an experiment in the wake of Nureyev’s sensational play with his own image. Dressed not in pearls but in black Adidas track suits (an inhabitation of ‘standard-issue’ clothing enforced not only for all workers in uniform but also for dancers in training and here, maybe also, lads on the town) dancers in Lads create a sculptural force-field of their own, one now expanded from the magnetic dyad of MBNo1. Made with and/or performed by dancers including, to date, Jessica Cooke, Thomas Dupal, Andrew Graham, New Kyd, J Neve Harrington, John Hoobyar, Samir Kennedy, Elena Rose Light, Christopher Matthews, Erik Nevin, Samuel Ozouf and Eve Stainton,[15] Lads consists of a slow-motion dance battle. Resembling a blissed-out game of Twister, one dancer dances, the other watches, and different dancers cycle in and out of that pairing. The dancing one lies on or hovers close to the floor as they shift, now languid, now crumpled, through a series of poses. Drawn from dance and art history, this repertoire of poses includes the opening silhouetted recline of Vaslav Nijinsky’s L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912), a role in which Nureyev famously thrived. The dancers then carry morphing artistic ghost-forms in their bodies as they move, offering glimpses of fleeting dance ancestors.

J Neve Harrington, with ghosts of Nijinsky and Nureyev, in the ‘Faune’ pose while performing Lads. Instagram post. 26 June 2021

The watching one, meanwhile, is engaged in a process J Neve Harrington (Neve from now on) described to me as “stalking an image”. They watch, circle and attend to the dancing one, pausing occasionally to take photos of the other on a smartphone and thus inhabit what Neve calls a “kind of voyeuristic space” and function as a kind of “buffer” between the dancing one and the audience who wander around, the audience watching on at this ritual of watching. As Neve explained to me, the watcher acts as a:

buffer between, but also an echo of the relationship between audience and the dancing figure. They model a kind of tighter, heightened version of the potential dynamic between audience and dancer, but one in which the documenting dancer is a kind of shield or mirror: echoing, reflecting, framing, obscuring…

These moves also initiate heart-whirring sonic interactions with a sound piece by Naoto Hiéda, a glitchy treatment of Air’s “Sexy Boy,” which speeds up, slows down and distorts in response to the movements of bodies in the physical space, both those of the dancers and those of the audience, should we dare to enter the field of movement and sound emanating from this glacial dance battle. But the work does not remain only in the physical space, as the images and short videos captured on the smartphone are posted to the work’s auxiliary performance space, Instagram, under the hashtag #lads, raiding insta’s more hetero-masculine stream of lads-tagged images with photos and clips of dancers doing queer things on the floor.

Speaking further with Neve about her experiences of performing the work (for which she also served as rehearsal director), drew my attention to a particular way in which Nureyev’s binary-skewing corporeal style invests this stage in Desire Cycle. As Neve explained to me when I asked what it feels like to dance this dance:

We are moving through a series of poses. But we are disguising from where the initiation of the movement comes. It’s a bodily experience that’s like underwater creatures, where force is distributed differently through the body. What I’m doing inside the dance is distributing tension through my body in an unfolding series of counter-balancing. None of the relations [of body to space, of weight to gravity, of each pose to the next] are binary; like up and down. It’s distributed in a more round way. And so no pathway is a straight line. Everything is a kind of a curve.

I am struck here by the extent to which Neve’s description feels to me like my own sensations of embodying ballet épaulement, where counter-posing and counter-twisting through torquing tensions in the body produces a feeling of curves over lines, of sighs over positions. It is impossible to tell from where the movement comes or at which place it stops. And it is here that Nureyev’s image appears again for me in Lads: in the remnants of an especially twisty épaulement that pulls the series of poses together, a queer stylistics of presenting ‘image’ in dance where lines twist, visions dissolve and any kind of movement-binary collapses in the process.

Neve’s reflections on performing Lads also helped me to see a dimension of this work that runs throughout Desire Cycle, and which I sensed as an audience member but that might manifest more intensely for those who dance it: the work’s creation of a particular kind of force-field of attention. As Neve explains of the lighting design (a spot-light on the watching ritual in the centre, darkness surrounding):

You’re in a pool of light. It’s quite delineated. It’s actually really difficult to see who’s beyond it. And because you can’t really grasp what’s going on with your eyes, you’re actually busy with what’s happening inside of that space.

She went on to reflect on the form of gaze to which this experience gives rise:

The gaze in Lads is really short-distance. It’s like being in a snow globe. When you’re the person who’s documenting, you’re only looking at the phone, the person who’s moving, the floor. You’re not looking at anything else. You have these few reference points that get reorganised. And there’s a tension there which, for me, is attention. Tension and attention come from the same root: what we reach for, what we stretch to attend.

Christopher Matthews and J Neve Harrington performing Lads in 2021. Photograph by Camilla Greenwell.

Neve’s idea that the work’s peculiarly focussed gaze is involved in the staging of ‘what we reach for’, speaks back to Halperin’s definition of the erotic in Plato: a force-field of desire. From outside the work, where I have stood, it does indeed seem like the two bodies we witness are in a snow globe, a world of their own, one we might dare to enter but for which a kind of daring is required. From inside the work a snow-globe proxemics creates forces of reaching-for, forces of desire, that are kept, and in turn keep its inhabitants, within. [16]

Act 3 – Queer(ing) MacMillan

Act 3 is both Desire Cycle’s final work (premiering in 2024) and the work representing the ‘late’ stage of the cycle, made for and with a group of dancers aged 60 and above who have lived through and beyond the life-stages represented in MBNo1 and Lads. In 2024, the performers of this work were: Bruce Currie, Donald Hutera, Roberto Ishii, John Charles Marshall, Andy Newman, Stephen Rowe, and Markus Trunk. With this group of performers, Chris in effect made the cycle’s final work with an ensemble of mentors, looking ahead with his collaborators towards potential futures he has yet personally to live. The work’s intergenerational communions travel far into its art inspirations and choreographic textures, too. Act 3 is a fitting late-stage moment in the cycle because it acknowledges many of the dance ancestors already accumulated in in MBNo1 and Lads and already discussed here. The Jacob’s Pillow bathrobes are back as dancers, otherwise dressed in white vests, shorts and sports socks, take on and off their robes throughout (more on this later). Nureyev, too, haunts this work, as a dance-elder who would have turned 86 just prior to this work’s first performance, had he survived the state violence that took his life as a queer man who died from AIDS complications in 1993. But Nureyev visits this work from across what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has achingly termed “the ontological crack between the living and the dead,” because he was also one of the first dancers to embody a ballet at the heart of Act 3’s explorations of desire: Romeo and Juliet by British choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, first performed in London in 1965 with the central roles danced by Nureyev and Fonteyn. It is on this work, specifically Chris’s and my mutual fascination with a weird phenomenon of dance-eroticism within it, that I reflect now as a way into the final part of my discussion, about Act 3 as a lesson in how desire yearns experientially for distance and can coalesce politically in community.

One of the most animated segments of mine and Chris’s conversation revolved around our shared strongly-held views about how un-sexy the ‘kiss’ moments are in MacMillan’s otherwise intensely erotic pas de deux in the ballet. For Chris, the problem was best expressed in the bedroom pas de deux opening Act 3 of ballet; for me, in the balcony scene closing Act 1. Both of these pas de deux involve entanglements of bodies, passionate comings-together and moving-aparts, in increasingly imaginative and acrobatic corporeal formations until, as the dance comes to a close, both scenes end in a somewhat awkward snog. Here’s what we said about this, having discovered that we had both for a long time been puzzled and/or disappointed by these moments in a ballet that we otherwise found quite sexy:

Chris: Desire is the intention; the wanting. For me when I watch MacMillan’s ballet, yeah it’s beautifully passionate, but the moment they’re in the embrace, I’m no longer satisfied.

Arabella: Yes! This is what I love about the pas de deux but also find odd: the most desire-filled choreography and performance is everything that happens before they kiss. Why do we have all this extraordinary bodily intercourse and then there’s just like this damp kiss at the end? What you’ve helped me understand, though, by saying desire is in the intention, the wanting, is that in the lead up to the kiss, they’re expressing their desire for something that’s yet to happen and that’s why the kiss feels like such a let-down.

Here are two screenshots of the bedroom pas de deux showing something of this observation. MacMillan’s choreography is performed here by the ballerina with whom it was originally made, Lynn Seymour,[19] partnered by David Hall, in 1979.

Screen shots from YouTube clip showing part of the documentary by Karin Altmann, Lynn Seymour: In a Class of her Own (1979) [20]

The first shot shows an ecstatic moment where pleasure seems to arise from the magnetic distance between the lovers (an upper distance extending between what we can see of their bodies anyway), the second shows the moment they finally meet fully to kiss at the end. Not so ecstatic. The desiring requires distance.

Chris confirmed that if anything from MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet ends up in Act 3, it is this very discovery about desire and distance in choreographic explorations of forbidden love. This discovery shows up no more clearly than in a gesture that acts a choreographic refrain through the piece, a link connecting the work’s series of duets. Around a mattress gather a group of men. One at a time, they approach and get onto the mattress to complete a dreamy lying-down dance, the mattress beneath both cradling and destabilising their bodies at they move. The others watch on. When it is time for the next dancer to approach the mattress and begin his own solo, a transition ritual occurs. The first soloist, now standing upright on the mattress, extends an up-turned palm in a ‘may I have this dance’ gesture, towards the newly arrived other. This second soloist reaches for his partner’s hand as he climbs onto the mattress beside him, but comes to pause in this reach just before their hands touch.

Donald Hutera and Markus Trunk performing Act 3 in 2024. Photograph by Gigi Giannella.

What ensues is a slow and quite precarious rotation of two bodies around an invisible axis; eyes fixed on the other like in that earlier dance of youth, hands hovering one above the other, creating an empty space magnetic in the distance between their touch. As Chris puts it: “they are looking at each other in the eyes but they never complete;” a visceral feeling that might be all the more tactile for the absence of touch.[21]

Cycling out: communities of desire

While Act 3’s choreographies of desire emanate most explicitly from these moments of intimate encounter in duet-form, what is also so clearly important about the work is its ensemble dynamics of mutual attention, and it is here that I find myself reflecting on the cycle as a whole in relation to investigations of community that buoy it throughout.

A moment of revelation during the making-process for Act 3 occurred when Chris’s friend, the artist and researcher Andrew Sanger, visited rehearsal to observe how the work was taking shape. While watching the series of mattress duets unfold, Sanger relayed back to the group how he saw the full ensemble of dancers remain, without prompting from Chris, ‘inside’ the work during each discrete duet even when not dancing, forming a group of observers staying with their collaborators’ efforts, watching intently and sharing the occasional hushed exchange about the style of each other’s moves. “This is the piece;” they all decided. “The community is present.” In the work’s final form, this part of the rehearsal culture is retained. The watching chorus – who remind me of the ever-expanding-through-gossip group of men interested in the discourses on love in Plato’s Symposium – put on their bathrobes and stay in the space while they watch each duet, keeping warm and summoning up the community ancestors Chris had found at Jacob’s Pillow in his youth.

As Donald Hutera, who danced in Act 3, remarks on the process of making this work together: “the camaraderie between us – the affection, respect and trust – were genuine and deep.”[22] Deriving from the Spanish camarada – ‘chamber mate’ – and similar etymologies invoking shared rooms, the word camaraderie is significant here. Describing a collective relationality based in a shared space,[23] a shared home through which comrades might together pass, Hutera suggests something at play across Desire Cycle most broadly: a field of transhistorical presence providing a space of communion for dancers across eras, across generations and even, as Sedgwick had it, across ‘the ontological crack between the living and the dead.’ If force-fields of desire are created in performances of Desire Cycle’s three pieces, they are force-fields open in this way to fleeting movements between past, present, future, evading the concrete capture of history but captivating attention in community.

Notes:

See the opening pages to Plato, Symposium, translated by Benjamin Jowett (1892).

David M Halperin, 'Plato And The Erotics Of Narrativity', in Julia Annas, James C Klagge, and Nicholas D Smith (eds.), Oxford Studies In Ancient Philosophy (Oxford, University of Oxford Press, 1992), pp. 50 & 53.

Paul Scolieri discusses the inaugural Jacob’s Pillow tea-party in his Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances. New York, (NY: Oxford University Press, 2020), p.290.

See for example Carolyn Merritt, “Marie Geneviève Van Goethem, aka ‘Little Dancer Aged Fourteen’,” ThinkingDance.net, 9 July 2019: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

Lionel Popkin, ‘The Complexities of Indian Dance at The Pillow’, PillowVoices: Dance Through Time S1:E25, 22 May 2021: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

A glimpse of these complex histories is given in Brian Schaefer, ‘The “Secret” Gay History of Jacob’s Pillow’, PillowVoices: Dance Through Time S1:E42, 29 October, 2022: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

Christopher Matthews, ‘My body’s no.1’, FormedView.com: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

Joan Acocella, ‘Wild Thing’, The New Yorker, October 1, 2007: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

Acocella, ‘Wild Thing’.

Chris has created an installation piece inspired by Nureyev’s stardom. A star is born...in a disco (2021) transforms a theatre dressing room into a small disco dancefloor replete with multi-coloured disco lights, Warhol-esque floating silver star balloons and summoning Nureyev’s legendary nights-out at Studio 54.

“Fonteyn and Nureyev sparkle in Le Corsaire at Covent Garden”, 5 November 1962, ‘By Our Ballet Critic’, archived at: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

The Rudolf Nureyev Foundation. ‘Le Corsaire’, Nureyev.Org: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

Jasbir K. Puar, Terrorist Assemblages : Homonationalism in Queer Times, (Duke University Press, 2007), p.75.

See the cover image and story about Nureyev’s Parisian apartment for the September 1985 issue of Architectural Digest. Mitchell Owens, “Dancer Rudolf Nureyev's 1985 Apartment in Paris Sweeps AD100 Designer Stephen Sills Off His Feet”, Architectural Digest 17 February 2020: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

Martin Hargreaves served as dramaturg and Shannon Stewart provided an outside eye in the development of the work.

My thanks to J. Neve Harrington for sharing her insights with me.

As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote two years before Nureyev’s death, in her talk for her friend Michael Lynch: “It’s been one of the great ideological triumphs of AIDS activism that, for a whole series of overlapping communities, any person living with AIDS is now visible, not only as someone dealing with a particular, difficult cluster of pathogens, but equally as someone who is by that very definition defined as a victim of state violence.” ‘White Glasses,’ in Tendencies, edited by Michèle Aina Barale, Jonathan Goldberg and Michael Moon, (New York, USA: Duke University Press, 1993), p. 261.

Sedgwick, ‘White Glasses,’ p. 257.

It is essential to acknowledge that MacMillan’s ballet was made principally in collaboration with the dancers Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable, whose rare artistry in the roles of Juliet and Romeo was ultimately subordinated by company management to the pull-power of the Fonteyn-Nureyev star partnership, in a controversial casting decision for the ballet’s opening night.

Gualtier Maldè, ‘Lynn Seymour & David Wall “Romeo and Juliet” Bedroom PDD’, YouTube, 13 April 2008: Link [Accessed 13 September 2024]

My thoughts about this moment in the work are very much informed by the writings of, and conversations with, my friend Royona Mitra, whose forthcoming book reframes dance ‘contact’ beyond touch. See: Royona Mitra, Unmaking Contact: Choreographing South Asian Touch, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2025). Mitra’s work is specifically located, bringing an anti-caste ethics to exploring contact in transnational South Asian choreographies. I find her theorization of contact as a choreographic and political phenomenon that might expand beyond touch, also compelling for thinking about intimate dance encounters more broadly, including this one in Act 3.

My thanks to Donald Hutera for permitting me to reproduce his insights here.

I also think out to the forms of community and camaraderie that converge around the theatre spaces in which Desire Cycle’s works are performed. It is important to acknowledge that at the time of writing, the venue in which all three of these works have been shown – Sadler’s Wells -- is under a cultural boycott in solidarity with the people of Palestine. To learn more about this campaign by Culture Workers Against Genocide and to join collective efforts encouraging arts institutions to take responsibility for their complicit investments and so enact a positive role in global liberation struggles, visit: Link